Executive Summary

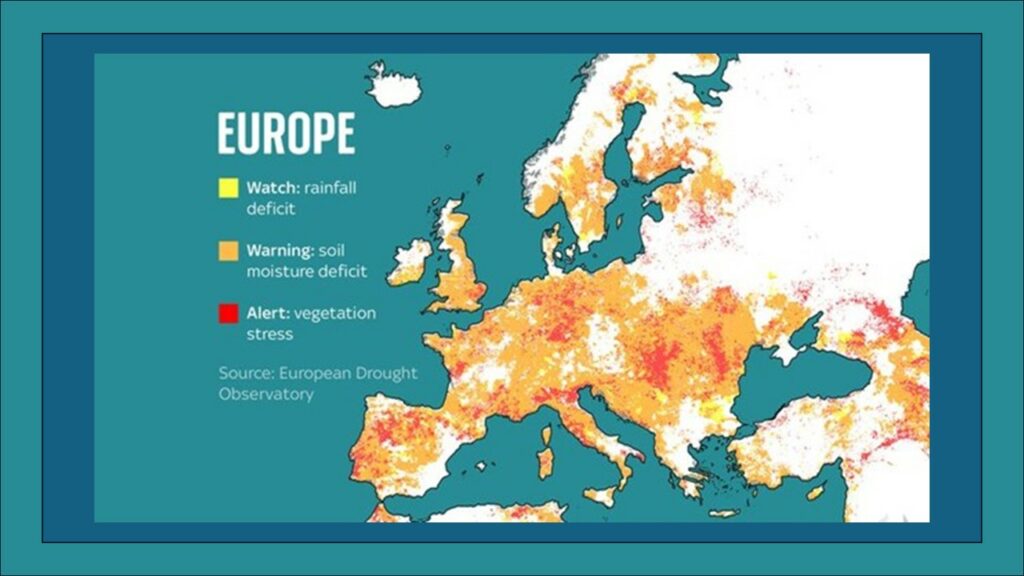

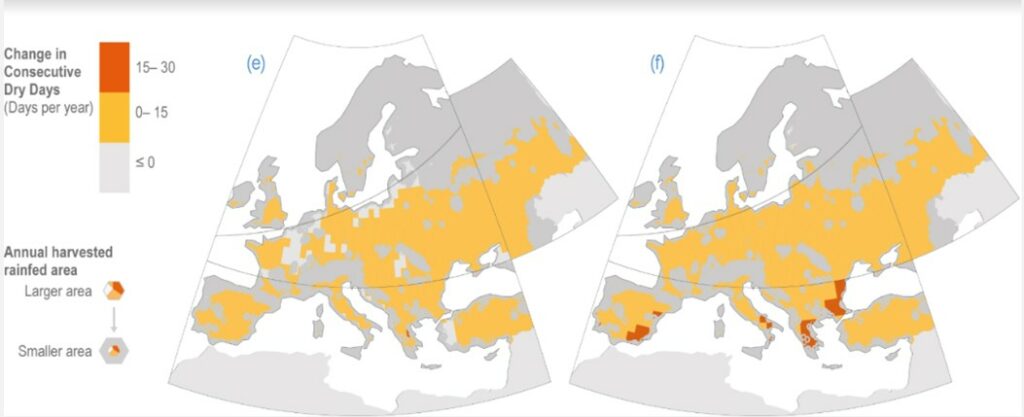

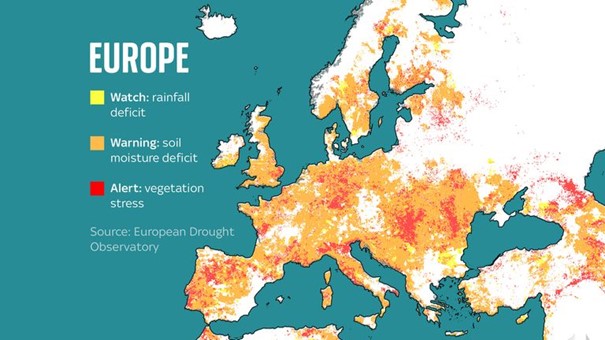

The State of the Climate in Europe 2022 report, issued by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), found that Europe is warming twice as fast as the global average due to climate change (WMO 2023). In particular, the Mediterranean has been identified as a “hotspot” particularly sensitive to the effects of global climate change due to rising temperatures and decreasing precipitation (Giorgi 2006; Giorgi and Lionello 2008; Lionello et al. 2012). As Europe’s agriculture faces escalating climate shocks, through prolonged droughts and heatwaves to erratic rainfall and soil degradation: decision-makers must transition from reactive crisis management to anticipatory, data-driven resilience.

Leveraging EO, climate indicators, and federated agricultural data spaces such as those developed under AgriDataValue offers a transformative opportunity to modernize agricultural planning and climate adaptation. This blog post intends to elaborate the reasons to establish an EU-wide policy framework enabling the operational integration of EO-based climate intelligence into agricultural risk management (RM), the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), and National Adaptation Strategies.

Context and strategic imperative

Agriculture accounts for over 10% of EU CO2 emissions. Yet, it remains one of the most climate-vulnerable sectors (EEA, 2024). Between 1980 and 2023, extreme weather events cost Europe’s agriculture over €487 billion in losses (European Parliament, 2023).

These challenges are expected to intensify: the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 6th Assessment Report (AR6 WGII, 2023) notes that “Risk of water scarcity will become high at 1.5°C and very high at 3°C GWL in Southern Europe (high confidence).” Therefore, Southern Europe is a climate hotspot where water stress, heatwaves, and land degradation will threaten productivity and food security.

EO and data-driven models already demonstrate their potential. Projects such as AgriDataValue, DestinE, and EO4AGRI have shown that integrating climate indicators (temperature anomalies, evapotranspiration, soil moisture, drought indices) into agricultural planning can support early warning, adaptive irrigation, and yield prediction. However, these innovations remain fragmented due to lack of standardization, governance frameworks, and incentives for data sharing.

The opportunity: from datasets to decision support systems (DSS)

Europe has made strategic investments in digital and space infrastructures, such as Copernicus, GALILEO, and the upcoming European Green Deal Data Space.

AgriDataValue builds upon this momentum through its federated Agri-Environmental Data Space, connecting satellite, the Internet of Things (IoT), and in-situ data without centralizing ownership. This model aligns with the EU Data Strategy (COM/2020/66), Data Act (Reg. 2023/2854), and the Data Governance Act (Reg. 2022/868), all promoting trustworthy, interoperable data ecosystems that preserve data sovereignty.

By operationalizing climate and EO data through the AgriDataValue framework, policymakers can:

- – Enable evidence-based CAP implementation, particularly for eco-schemes and drought monitoring.

- – Support climate-informed insurance and credit instruments, reducing fiscal pressure from disaster compensations.

- – Strengthen multi-hazard early warning systems, as urged by the UNDRR Sendai Framework (2015–2030) and the United Nations Early Warnings for All Initiative (2023).

Key barriers to address

Despite technological maturity, 3 systemic bottlenecks prevent large-scale integration:

1.Governance fragmentation: Data ownership remains unclear across EO providers, private platforms, and farmers. National adaptation and CAP agencies often lack coherent governance mechanisms for integrating climate intelligence.

2. Uneven access and incentives: Smallholders and cooperatives rarely have access to tailored EO analytics. Without clear economic incentives, many refrain from sharing or using data (OECD, Data Governance in Agri-Food, 2022).

3. Lack of harmonized climate indicators: The absence of an EU-wide taxonomy for agri-climate indicators limits interoperability and comparability across regions. FAO’s Agro-Environmental Indicators and Eurostat’s Agri-Environmental Data Framework remain underutilized for operational planning.

Policy recommendations

A. Establish an EU framework for climate-informed agriculture: Create a dedicated “EU Climate Intelligence for Agriculture” initiative under the Green Deal Data Space and the Common European Agricultural Data Space (CEADS).

It should provide:

- – A standardized set of climate indicators for agricultural decision-making, aligned with FAO, WMO, and EEA methodologies.

- – Open-access geospatial tools derived from Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) and AgriDataValue platforms.

- – Integration of climate services into CAP Strategic Plans and National Adaptation Plans.

B. Incentivize data sharing and use through CAP instruments: Use eco-schemes and conditionality payments to reward farms that integrate EO-based risk assessments or adopt predictive drought management tools. Encourage data cooperatives and public–private partnerships (PPPs) to ensure equitable access to analytics and training (OECD, Enhancing Resilience in Agriculture, 2021).

C. Embed governance and ethics-by-design: Adopt governance models inspired by AgriDataValue’s federated architecture, ensuring trust, traceability, and consent management under the EU AI Act (2024) and GDPR. Encourage Member States to establish national climate data coordinators to ensure local interoperability within CEADS.

D. Link climate intelligence with disaster risk reduction and finance: Integrate AgriDataValue’s outputs into the EU Civil Protection Mechanism and European Drought Observatory.

Support parametric insurance models and climate-linked financing tools through the European Investment Bank (EIB) and European Innovation Council (EIC). Promote synergies with the United Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC) Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture (2022) and OECD-FAO Joint Working Party on Agriculture and Climate (2023-2032).

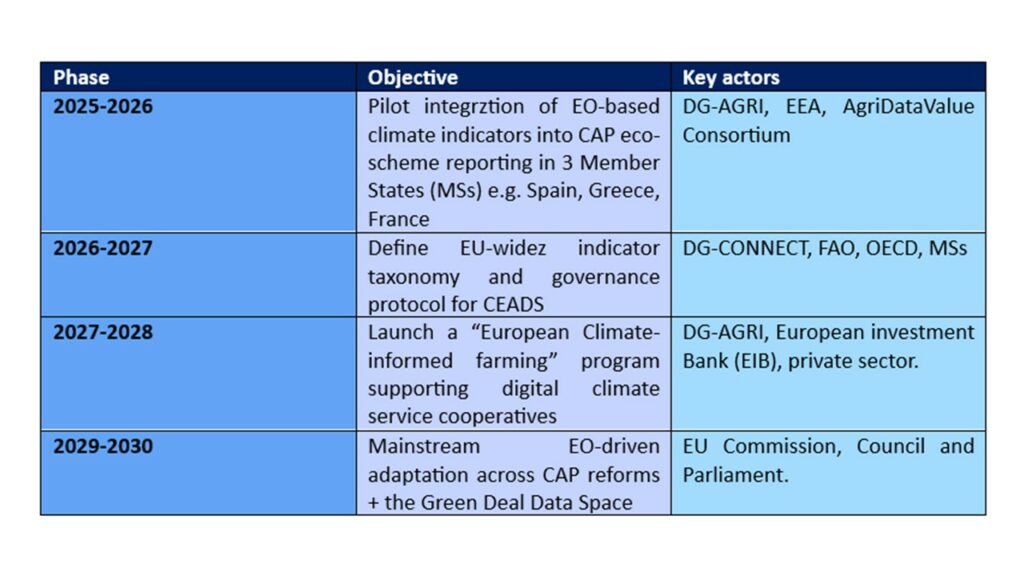

Implementation Roadmap (2025–2030)

Conclusion

The transition to a climate-informed agricultural system is not merely technical: it is institutional, economic, and political. Initiatives like AgriDataValue demonstrate that federated data architectures and EO-based indicators can form the backbone of a resilient, equitable agricultural future. Nevertheless, realizing this potential requires policy alignment, governance innovation, and targeted incentives. By acting now, Europe can turn data into foresight. Foresight into prevention. And prevention into sustainable resilience. In doing so, the European Union would ensure its farmers not only survive climate change but thrive through it.

References and sources:

- 50by40. (2022). 50by40 Network submission to the Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture (KJWA). [PDF] May. Link: https://50by40.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/50by40KJWA_May2022.pdf

- European Civil Protection Mechanism. (Regulation (EU) No 1313/2013). Link: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013D1313

- European Commission. (2020). A European strategy for data (COM(2020) 66 final).

- European Drought Observatory (EDO), Joint Research Centre, European Commission. Link: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/european-and-global-drought-observatories/current-drought-situation-europe_en

- European Investment Bank (EIB) Group. (2025). Climate Bank Roadmap 2021–2025: An independent evaluation. Link : https://www.eif.org/news_centre/publications/eibg-climate-bank-roadmap-2021-2025-evaluation.pdf

- European Parliament / DG for Structural and Cohesion Policies. (2023). The impact of extreme climate events on agricultural production and growth in the EU. Link: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2023/733115/IPOL_STU(2023)733115_EN.pdf

- Giorgi, F. (2006). Climate change hot-spots. Geophysical Research Letters, 33, L08707. Link: https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1029/2006GL025734

- Giorgi, F., & Lionello, P. (2008). Climate change projections for the Mediterranean region. Global and Planetary Change, 63(2–3), 90–104. Link: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2007.09.005

- OECD. (2020). Strengthening Agricultural Resilience in the Face of Multiple Risks. Link

- OECD/FAO. (2023). OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2023–2032. OECD Publishing, Paris. Link: https://doi.org/10.1787/08801ab7-en.

- Regulation (EU) 2022/868. Data Governance Act. Link: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022R0868

- Regulation (EU) 2023/2854. Data Act. Link: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32022R0868

- Santeramo, F.G., Balezentis, T., & Tappi, M. (2025). Weather and Yield Index-Based Insurance Schemes in the EU Agriculture: A Focus on the Agri-CAT Fund. Link: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-80574-5_3

- UNDRR. (2015). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. Link: https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030

- UNDRR. (2023). Early Warnings for All initiative. Link: https://www.undrr.org/implementing-sendai-framework/sendai-framework-action/early-warnings-for-all

- UNFCCC. (2021). Koronivia Joint Work on Agriculture. Link : https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/sb2021_03a01_adv.pdf